https://inuit.uqam.ca/iu/person/freeman-minnie-aodla

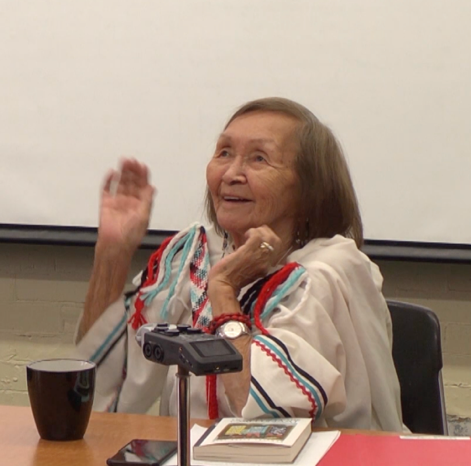

1936 -

Mini[1] Aodla Freeman is an Inuit writer, editor, translator, producer, and respected elder. She has written several poems, plays and a memoir, Life Among the Qallunaat (1978), which was recently republished in 2015.

Aodla Freeman was born to parents Malla and Thomas Aodla in 1936 on Cape Hope Island[2] into a community founded by her grandfather, George Weetaltuk (1859-1957) around the turn of the twentieth century. She grew up between her family’s summer and winter homes, in Old Factory (Niuuissak) and Cape Hope respectively (both communities are now uninhabited). She spent her childhood primarily with her brother and her paternal grandparents: her mother died when she was only a toddler and her father’s job, which involved navigating the Hudson and James Bay islands for employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company and Frères Stores, required him to spend longer periods of time away from his family.

In the spring of 1943, the family travelled to Moosonee and, that September, Aodla Freeman was enrolled in the Bishop Horden School in Moose Factory, Ontario. Shortly thereafter, she attended a Catholic school in Fort George (Chisasibi), Quebec and, at age sixteen, she began nurse’s training at the nearby Ste. Therese School. She was later diagnosed with tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium in Hamilton, Ontario. Despite being prescribed bedrest there, she was asked to translate between nurses, doctors, and Inuit and Cree patients, thanks to her fluency in both Inuktitut and Cree, a language she had learnt from the other girls during her time at the Bishop Horden School. Eventually, Aodla Freeman became accepted as a staff member at the sanatorium; she moved in with the rest of the nurses and began to study and train with them. A year before becoming certified as a nurse, she returned home at the request of her family but, after a brief visit with her grandmother, she headed south again in order to avoid an arranged marriage that had become undesirable.[3] She found work as a nanny for a few years in Moose Factory before being hired by a local Anglican school, first to do laundry and then to supervise forty-four intermediate students.

In 1957, she was recruited to work as a translator for the Canadian government in the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources in Ottawa. Though nearly all of her jobs took her far from home, Aodla Freeman made efforts to visit her family on a yearly basis. She recounts these visits, as well as the pronounced differences between southern Canadian society and her own culture in her memoir, Life Among the Qallunaat,[4] which she published in 1978. Her book not only details her life and travels throughout northern Canada and her eventual move to the south; it also continually returns to and reflects on Inuit worldviews regarding a variety of topics ranging from child-rearing and rule-making to social decorum and intimacy, from concepts of time and space to beauty standards and prejudice, from homesickness and loss to humour and happiness, and from memory and storytelling to politics and freedom.

Life was initially anticipated to be a best-seller but, upon its publication, half of its 6,254 copies were bought out by the government and hidden in a basement in an attempt to prevent stories of forced relocation and residential schools from surfacing and reflecting poorly on the Canadian government. Ironically, Aodla Freeman never outspokenly criticized residential schools in her book, though she later mentions wishing she had.[5] Her memoir instead offers up candid and nuanced reflections on her experiences in the schools both as a student and later as a teacher. Life was republished in 2015 as part of a First Voices First Texts project aimed at recovering and making available lost or underappreciated works by Indigenous individuals.[6]

Aodla Freeman’s career took her in a multitude of directions. She has published work in several genres: her poems and short stories have been featured in Canadian Children’s Annual and the International Women’s Year travelling exhibition, and her play, Survival in the South, was produced for the Dominion Drama Festival (1971) and staged two years later at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. From 1973-1979, she served as Native Cultural Advisor and narrator for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). She has also been an Assistant Editor for the magazine, Inuit Today, founder and producer for the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation, and Executive Secretary of the Land Claims Secretariat of the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada. In 1996, she co-edited a book with Odette Leroux and Marion E. Jackson called Inuit Women Artists, which features the artwork, reflections, and memories of several Inuit women from Cape Dorset. She has also served as an elder at Bowden Institution, a prison in Alberta, and has been actively involved in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. More recently, she appeared in and narrated a 29-minute documentary about the history of Cape Hope called Nunaaluk: A Forgotten Story (2014), and she is in the process of working on a book about the history of the Inuit of James Bay, also entitled Nunaaluk. Aodla Freeman currently lives in Edmonton where she is a well-known and dearly loved community elder.

Selected Readings:

Freeman, Minnie Aodla. “Introduction.” Inuit Women Artists: Voices from Cape Dorset. Edited by Odette Leroux, Marion E. Jackson, and Minnie Aodla Freeman, Chronicle Books, 1996.

Freeman, Mini Aodla. Life Among the Qallunaat. Ed. Keavy Martin et al., U of Manitoba P, 2015.

Freeman, Minnie Aodla. “Survival in the South.” Paper Stays Put: A Collection of Inuit Writing. Edited by Robin Gedalof, with drawings by Alootook Ipellie. Hurtig, 1980. pp.101-112.

Nunaaluk: A Forgotten Story. Directed by Louise Abbott, COTA, 2014.

Works Cited:

Freeman, Mini Aodla. Life Among the Qallunaat. Ed. Keavy Martin et al., U of Manitoba P, 2015.

Fredrickson, Rebecca, et al. “From Qallunaat to James Bay: An Interview with Mini Aodla Freeman, Keavy Martin, Julie Rak, and Norma Dunning.” Canadian Literature, no. 226, Autumn 2015, pp. 112-124.

Grace, Sherill, E. “Writing, Re-Writing, and Writing Back.” Canada and the Idea of the North. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2002, pp. 229-260.

Martin, Keavy and Norma Dunning. “One Day Somebody is Going to Forget: A Conversation with Mini Aodla Freeman.” Life Among the Qallunaat. Ed. Keavy Martin et al., U of Manitoba P, 2015.

Rak, Julie, et al. “Life After Life Among the Qallunaat.” Life Among the Qallunaat. Ed. Keavy Martin et al., U of Manitoba P, 2015.

Additional Resources:

For an analysis of current trends in Inuit writing, see:

Henitiuk, Valerie. “‘Memory Is so Different Now’: The Translation and Circulation of Inuit-Canadian Literature in English and French.” Contemporary Approaches to Translation Theory and Practice, Routledge, London, 2020.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429402029-5/memory-

different-translation-circulation-inuit-canadian-literature-english-french-

valerie-henitiuk

Abstract

Inuit, even more marginalized than the First Nations or Métis, settled along what is now northern Canada some 4000-6000 years ago. They have a centuries-long history of orature (legends, myths, songs, etc.), although literacy is a more recent arrival. Interest in this traditionally nomadic, socially complex, and richly imaginative culture has been increasing rapidly in the past few years, with the emergence of prize-winning films by Zacharias Kunuk and others; the second edition of Life Among the Qallunaat (the autobiography of Mini Freeman, a quadrilingual Inuk who worked as a translator in Ottawa for some 20 years); and the publication in 2013 of an English version of what has been called the first Inuktitut novel, first begun by a woman in the 1950s. This paper will examine a few recent developments in the present-day circulation of the traditions of one Canada’s no-longer-quite-so-invisible ‘invisible minorities,’ with a particular focus on Sanaaq by Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk, who has been

referred to as ‘the accidental Inuit novelist (Martin, 2014).

Endnotes:

[1] Mini’s name has been Anglicized on books and on other official documents (including her birth and marriage certificates) as “Minnie,” but the correct orthography of her name is M-i-n-i, which, in Inuktitut, means “gentle rain” (Fredrickson et al. 120).

[2] The Inuit call Cape Hope Island Nunaaluk, but Mini Aodla Freeman also refers to this island as Weetaltuk Island in Life Among the Qallunaat.

[3] According to Inuit traditions, a future spouse is chosen for a child at the time of his/her birth. While these arrangements do generally lead to marriage, they are not set in stone; other arrangements can be made if the original one is no longer desirable. For a more detailed explanation of arranged marriages in Inuit culture, see Aodla Freeman’s reflection on the subject in Life Among the Qallunaat, pp. 31-32, 70-71, 204-206, 231-232.

[4] Aodla Freeman explains that the word, qallunaat, literally means “people who pamper their eyebrows” (86), but it can also connote a sense of avarice, and can imply that one is fussy with nature, materialistic, respectable, fearsome, alluring, and/or magical (86-87). It is commonly used by Inuit communities to refer to “Southerners,” “white people,” “English speakers,” or those living in the southern regions of Canada (Martin xiii). Because of this title, Aodla Freeman’s memoir has been described by some scholars as a reverse-ethnography that inverts popular, Western representations of Indigenous peoples (like those found in Bernhard Adolph Hantzsch’s Life Among the Eskimos) by instead portraying Western society from an Indigenous perspective. See Martin and Dunning’s “One Day Somebody is Going to Forget” (xiv-xv) and Rak et al.’s “Life after Life Among the Qallunaat” (265-266) for more on Life’s title; see Sherill E. Grace’s “Writing, Re-Writing, and Writing Back” for a discussion on the genre of reverse-ethnography.

[5] In her description of how Northern Affairs was attempting to contain the testimonies of residential school survivors around the time of Life’s initial publication in 1978, Aodla Freeman speculates that the government most likely kept her book out of circulation because “they thought I wrote something bad about residential schools, which I should have, but I didn’t” (Aodla Freeman qtd. in Martin, xvi, italics in original).

[6] Martin’s First Voices First Texts edition differs from the first edition published by Hurtig in 1978 because it is less heavily edited and restores much of Aodla Freeman’s original manuscript. For more on the memoir’s different editions, see Rak et al.’s “Life,” pp. 270-273.

Alootook Ipellie entry by Lara Estlin, July 2020. Lara completed her BA in the Department of English at SFU and then went on to complete her MA (English) at UBC. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2018 to 2020.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Additional Resources collected by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli completed his M.Mus. at McGill University in June 2024.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca regarding any comments or corrections at dhr@sfu.ca.