https://nouvelles.ulaval.ca/2022/06/06/sanaaq-revoit-le-jour-dans-une-nouvelle-edition-a:cf087fdc-7c82-4138-8afd-a697f3714337

1931 - 30 April 2007

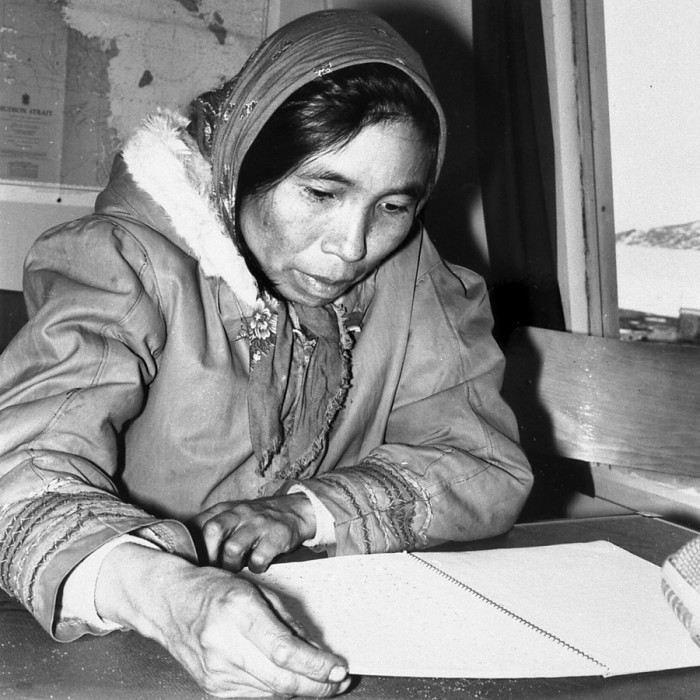

Mitiarjuk Attasie Nappaaluk (also known as Salome Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk) (Martin) was born in 1931 near Kangiqsujuaq, in Nunavik, northern Quebec. She was the eldest child. She had no formal schooling, but was educated by her mother and elder female relatives in traditional female occupations and, unusually, by her father as well. Having no sons, her father instructed her in the secrets of hunting and other typically male tasks and she often hunted on her own. In the Inuit culture, she belonged to a “third sex” or gender, neither male or female. This qualified Mitiarjuk as a mediator between sexes and different generations (d’Anglure vii).

At the age of 16, Nappaaluk, known to be very skillful, was courted by many young men. She chose the youngest suitor who agreed to move in with her family and take her place as primary provider. This was unusual, as most Inuit women went to live with their husbands’ families after marriage. She devoted several years to having children and caring for her family. In her early twenties, renowned for her creativity, she was asked to assist some Catholic missionaries who were interested in studying the Inuit language. Mitiarjuk was an invaluable assistant, initially helping Father Lucien Schneider produce an Inuit - French dictionary. In return, she learned to write in syllabics, a writing system created by the Wesleyan missionaries to advance the conversion of Indigenous people and adopted by other missionaries because it was easy to learn (d’Anglure vii). Later on, Father Robert Lechat, wishing to improve his language skills, asked

her to write down as many words and phrases she could think of. Nappaaluk recorded all the normal daily phrases she could think of but soon became bored. Using syllabics, creating her own symbols, and demonstrating the narrative style of her own people, she began to write the story of a female protagonist, Sanaaq, and a small group of Inuit families, describing events that occurred in the 1920s (Martin). She wrote the first part of this novel in the early 1950s, then stopped writing for several years due to an extended stay in the hospital and the transfer of Father Lechat to a new area.

She met Bernard Saladin d’Anglure, a French anthropologist in 1961; he convinced her to begin working on the book again. This book became the focus of Saladin d’Anglure’s scholarly work. He returned to Kangiqsujuaq in 1965 in order to translate the book from Inuktituut into French. Mitiarjuk helped him add punctuation, explained difficult passages, and identified plants and animals. During this six-year period she completed this work and wrote a sequel, which is in the process of being translated now (d’Anglure x). In 1977 she was featured in the television series Femmes d’aujourd’hui as a writer and an informant on Inuit culture and language. Her novel Sanaaq was published in 1984 in standard syllabics, fully illustrated, with funding from Ministère des affaires culturelles of Quebec. This version was distributed to all the Inuit schools in Northern Canada and is now out of print. Mitiarjuk kept 50 copies of this version to present to her many descendants. In 2002 a French translation of Sanaaq was published followed by an English version in 2014, bringing Mitiarjuk’s work to a much wider audience. She was a member of the Inuttitut Language Commission of Nunavik and authored 22 books to be used for teaching and helped to develop a curriculum for the Kativik School Board (The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General 2012). Nappaaluk also created an Inuttitut encyclopedia of Inuit traditional knowledge and translated Catholic prayer books into Inuttitut.

Mitiarjuk has earned a great deal of recognition as a writer and a scholar. In 1999 the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation presented her with the National Award for Excellence. She earned a PhD from McGill University for her work in advancing the teaching of Nunavik’s language and culture (d’Anglure vii). In 2001 UNESCO honoured her literary works at an international conference of Indigenous writers in Paris. On May 14, 2004 Mitiarjuk was named to the Order of Canada.

Mitiarjuk was a well known and respected Elder and her works were celebrated in her community; as well as her writing giving a precise and detailed account of Inuit life she also provided an insider female point of view, something that was previously nonexistent in literature by or about the Inuit people.

Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk passed away at her home in Kangirsujuaq on April 30, 2007 after a long illness. She was 78.

Selected Readings:

Nappaaluk, Mitiarjuk. Qimminuulingajut ilumiutartangit. Montreal: Kativik School Board, n.d.

---. Sanaaq: An Inuit Novel. Transliterated and translated from Inuktitut to French by Bernard Saladin D'Anglure, Translated from French into English by Peter Frost. U of Manitoba P. 2014.

---. Qupirruit. Montreal: Kativik School Board, 1987.

---. Sanaakkut Piusiviningita unikkausinnguangat. Edited by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure. Inuksiutiit Katimajiit, 1984.

---. Tarrkii piniarningillu. Montreal: Kativik School Board, 1997.

---. Tininnimiutaait. Montreal: Kativik School Board, n.d.

---. Silaup piusingit inuit nunangani. Montreal Kativik School Board, n.d.

Works Cited:

D’Anglure, Bernard Saladin. Foreword. Sanaaq: An Inuit Novel. By Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk. 2014.

Martin, Keavy. "Arctic Solitude: Mitiarjuk’s Sanaaq and the Politics of Translation in Inuit Literature." Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne [online], vol. 35, no. 2, 2010, n. pag. Web. 17 Apr. 2018.

The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General. “The Governor General of Canada.” The Governor General of Canada > Find a Recipient, 6 July 2012, www.gg.ca/honour.aspx?id=469&t=12&ln=Nappaaluk.

Additional Resources:

For an analysis of current trends in Inuit writing, see:

Henitiuk, Valerie. “‘Memory Is so Different Now’: The Translation and Circulation of Inuit-Canadian Literature in English and French.” Contemporary Approaches to Translation Theory and Practice, Routledge, London, 2020. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429402029-5/memory-different-translation-circulation-inuit-canadian-literature-english-french-valerie-henitiuk

Abstract

Inuit, even more marginalized than the First Nations or Métis, settled along what is now northern Canada some 4000-6000 years ago. They have a centuries-long history of orature (legends, myths, songs, etc.), although literacy is a more recent arrival. Interest in this traditionally nomadic, socially complex, and richly imaginative culture has been increasing rapidly in the past few years, with the emergence of prize-winning films by Zacharias Kunuk and others; the second edition of Life Among the Qallunaat (the autobiography of Mini Freeman, a quadrilingual Inuk who worked as a translator in Ottawa for some 20 years); and the publication in 2013 of an English version of what has been called the first Inuktitut novel, first begun by a woman in the 1950s. This paper will examine a few recent developments in the present-day circulation of the traditions of one Canada’s no-longer-quite-so-invisible ‘invisible minorities,’ with a particular focus on Sanaaq by Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk, who has been referred to as ‘the accidental Inuit novelist.’ (Martin, 2014)

For a discussion of the relationship between Indigenous and settlers when translating Indigenous texts, see:

Henitiuk, Valerie, and Marc-Antoine Mahieu. “‘who will write for the Inuit?’” Tusaaji: A Translation Review, vol. 8, no. 1, 3 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.25071/1925-5624.40422.

Abstract

This article examines the circumstances surrounding the first publication of an Indigenous novel in Canada, namely Uumajursiutik unaatuinnamut by Markoosie Patsauq, in 1969-70 It describes the context of the federal

government’s cultural policy, in particular within the then Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, and how this impacted relations with Inuit generally speaking, but also how it set the stage for bureaucratic

involvement in the production of an English adaptation of Patsauq’s text, widely known today as Harpoon of the Hunter. Finally, we present our own rigorous new translations, titled Hunter with Harpoon/Chasseur au harpon,

done in collaboration with the author and based on his original Inuktitut manuscript, suggesting some more ethical practices for working with Indigenous source texts.

For a study of the effects of economic pressures on Inuit hunters, see:

Hillemann, Friederike, et al. “Socio-economic predictors of Inuit hunting choices and their implications for climate change adaptation.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 378, no. 1889, 18 Sept. 2023,

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0395.

Abstract

In the Arctic, seasonal variation in the accessibility of the land, sea ice and open waters influences which resources can be harvested safely and efficiently. Climate stressors are also increasingly affecting access to subsistence resources. Within Inuit communities, people differ in their involvement with subsistence activities, but little is known about how engagement in the cash economy (time and money available) and other socio-economic factors shape the food production choices of Inuit harvesters, and their ability to adapt to rapid ecological change. We analyse 281 foraging trips involving 23 Inuit harvesters from Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik, Canada using a Bayesian approach modelling both patch choice and within-patch success. Gender and income predict Inuit harvest strategies: while men, especially men from low-income households, often visit patches with a relatively low success probability, women and high-income hunters generally have a higher propensity to choose low-risk patches. Inland hunting, marine hunting and fishing differ in the required equipment and effort, and hunters may have to shift their subsistence activities if certain patches become less profitable or less safe owing to high costs of transportation or climate change (e.g. navigate larger areas inland instead of targeting seals on the sea ice). Our finding that household income predicts patch choice suggests that the capacity to maintain access to country foods depends on engagement with the cash economy.

For an analysis of relationships between Indigenous Peoples and urban environments, see:

Marceau, Stéphane Guimont, et al. “Settler urbanization and indigenous resistance: Uncovering an ongoing palimpsest in Montreal’s Cabot Square.” Urban History Review, vol. 51, no. 2, 1 Sept. 2023, pp. 310–333, https://doi.org/10.3138/uhr-2022-0035.

Abstract

This article proposes to study a public square in Montreal, Québec, Canada, to illustrate how different processes of colonization, marginalization, and resistance take place in the city. The study of Cabot Square demonstrates the layers of Indigenous displacement and reappropriation that form the palimpsest inscribed in urban spaces. The authors shed new light on the contemporary context by studying it through the scale of a place and reinserting it in the context of settler colonialism in which social, political, and economic relations in Canada are deeply interwoven. Cities play a major role in colonial dynamics and in the processes of marginalization in a colonial division of space that places certain populations outside the spaces of power. Cabot Square is inscribed in these dynamics, but it is also a site of reappropriation, since services for people experiencing houselessness, cultural activities, and social economy projects intersect there, placing this public place at the heart of daily encounters. The study of Cabot Square as a place of diverse and often contradictory relationships, stories, and practices of urban place-making and Indigenous place-keeping reveals layers of colonialism and Indigenous resistance that overlap through history and interact to form the current cityscape in the Square and beyond. With this article, the authors aim to acknowledge the tensions and complexities of place-making within a settler-colonial context where Indigenous histories and meanings of places not only have been erased by colonial power but also kept alive as much as possible by Indigenous communities through place-keeping.

For a discussion of language and translation challenges around Indigenous and settler languages, see:

Brouwer, Malou. "Indigenous Literatures at the Crossroads of Languages: Approaches and Avenues." Alternative francophone, vol. 3, no. 3, 2023, pp. 10–31.

https://doi.org/10.29173/af29492

Abstract

This article examines critical discourses and approaches for the study of Indigenous literatures across languages. On the one hand, it investigates how the French-English divide is challenged by Indigenous authors and how it has been and can be further dealt with in Indigenous literary studies (ILS). On the other hand, it pays attention to the centrality and revitalization of Indigenous languages as they challenge colonial languages, complicate the French-English divide in ILS, and center Indigenous experiences. Engaging with the question “what approaches can scholars, teachers, and students in Indigenous literary studies use for the study of Indigenous literatures at the crossroads of languages?”, I highlight multilingual work by Indigenous authors, collect resources that directly engage Indigenous literatures from a (multi)language perspective, and gather approaches that can be helpful in developing a framework for the study of the multilingual corpus of Indigenous literatures.

Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk entry by Kimberley John in September 2018. Kimberley is an alumnus of SFU, graduating with a Double Major in Health Sciences and Indigenous Studies. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2016 to 2020.

Additional Resources by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli is an alumnus of McGill University, graduating with an M.Mus. in Jazz Performance in Summer 2024.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca regarding any comments or corrections at dhr@sfu.ca.