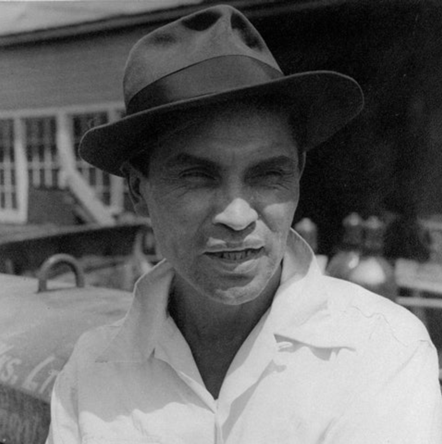

Museum Of Anthropology (MOA) 2005-001-393c

1905 - 1988

George Clutesi of the Tseshaht Nation was a writer, an artist, an actor, and a teacher. Through his lifelong endeavors he sought to portray the rich values and teachings of his people in contrast to existing literature that he felt only reiterated “the sometimes romantic aspects of a nearly forgotten culture” (Clutesi 9). He was born in 1905 in the village maaktii (Port Alberni) to Charlie and Katherine Clutesi. His mother passed away when he was four years old and he was raised by his father and aunts until he was old enough to be taken away to school. He remembered the traumatic episode of his father crying and throwing rocks at him, forcing him to leave (Tseshaht). Clutesi attended Alberni Indian residential school for eleven years. He was a shy, quiet child, often in poor health, held in an institution that had the sole purpose of separating children from their culture; he found solace in his art despite being told by the principal that artists were “terrible, sinful people [and] he must forget it” ("Get Your Bannock and Tea" 22:48). He did not.

After finishing school Clutesi worked for many years as a commercial fisherman. He married Margaret Lauder and raised six children and many foster children with her. He was employed as a pile driver on Vancouver Island when he broke his back in a construction accident in 1943. During his seven-year convalescence, unemployed, he returned to his art, developing a distinct style. He also began writing. He met Ira Dilworth, a chief executive at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and agreed to do a series of radio programs narrating traditional Tseshaht stories aimed at young listeners. Dilworth introduced Clutesi to Emily Carr and although they did not know each other for very long, he and his wife visited with her several times at her home and Carr left him her unused canvases and oil paints in her will when she passed away in 1945. During this time Clutesi was asked to lecture for several courses at the University of British Columbia and he taught a few summer courses.

In 1947, Clutesi began writing for the just-founded newspaper, The Native Voice. He wrote inspirational essays that described Tseshaht folklore handed down from generation to generation. In 1949 he hitchhiked to Victoria in order to address the Royal Commission on the National Development of Arts, Letters and Sciences, chaired by Vincent Massey, and asked his permission to practice traditional singing and dancing. At the time these practices were illegal according to the Indian Act. Massey instructed him to “go home and sing”[1] (Tseshaht). At this time Clutesi was employed as a janitor at the Alberni Indian Residential School and he began to teach the students Tseshaht songs and dances. At first there was some resistance, because the school had always promoted these traditions as “primitive and undesirable” (Tseshaht), but Clutesi persisted; he began a dance group that was invited to perform for Princess Elizabeth when she visited Victoria in 1951. Clutesi wanted what his people had lived for to be revived and remembered.

Clutesi was approached by Gray Campbell, a publisher from Sidney to put together a book as a centennial project. According to Campbell, when he arrived at his house, Clutesi was on the roof repairing it and understandably wary of white men since attending residential school, would not come down to speak with him (Aboriginality 60). Campbell was not deterred and climbed up to speak to him. A year later Clutesi contacted Campbell and they made arrangements for his first book, Son of Raven, Son of Deer (1967), a collection of Tseshaht short stories, which Clutesi illustrated himself. Clutesi hoped that this book would reach the “more sympathetic, more reasoning segment of the non-Indians, who may have some willingness to [understand] the culture of the true Indian, whose mind was imaginative, romantic and resourceful” (Clutesi 9). The book garnered attention and commercial success. Clutesi followed it with Potlatch in 1969, a work that brought to life the ceremony of the Potlatch, a word derived from the Nootka verb Pachitle, which means “to give” (citation). The Potlatch along with other ceremonies, had been declared illegal from 1885 to 1951.

In 1967, Clutesi was commissioned to create a large mural for the Indian pavilion at Expo ‘67 in Montreal. This earned him widespread recognition as an artist. He received an Honorary Doctorate of Law from the University of Victoria in 1971. In 1973, he received the Order of Canada for his contributions to writing, art and the preservation of Indigenous culture.

Clutesi added acting to his repertoire in the 1970s, beginning with appearances on several television shows, documentaries and dramatic series, and then expanding to several movie roles. He won an ACTRA award for his performance in Dreamspeaker (1977).

George Clutesi passed away in Victoria on 27 February 1988 at the age of 83. His final book, Stand Tall, My Son, a story of west coast First Nations society and how it changed with the arrival of the Europeans, was published posthumously in 1990, according to his wishes.

In his early years of writing, some Tseshaht members believed he was selling out their culture. A nephew of Clutesi, Randy Fred, wrote in memorial “I remember Uncle George was so very gentle. His voice had a bit of a rasp due to tuberculosis from his younger years.” Fred wrote about Clutesi’s first book, “When Son of Raven, Son of Deer was first published he was far from being a hero on our reserve. Slowly the feelings of Tseshaht people changed up to the point of pride for his accomplishments. Now it is well understood he was instrumental in preserving and promoting Tseshaht culture” (ABC Bookworld).

Selected Readings:

George Clutesi. Son of Raven, Son of Deer: Fables of the Tse-Shaht People. Gray’s Publishing, 1967.

---. Potlatch. Gray’s Publishing, 1969.

---. Stand Tall, My Son. Newport Bay Publishing, 1990.

Works Cited:

“Aboriginal Authors Art Essentials.” ABC BookWorld, https://abcbookworld.com/scripter/scripter-7046/.

Clutesi, George. Son of Raven, Son of Deer: Fables of the Tse-Shaht People. Illus. George Clutesi. Gray’s Publishing, 1967.

“George Clutesi Royal Commission testimony re-discovered.” Ha-Shilth-Sa, 28 Mar. 2017, https://www.hashilthsa.com/news/2012-03-15/george-clutesi-royal-commission-testimony-re-discovered.

“George Clutesi.” Tseshaht First Nation, http://www.tseshaht.com/history-

culture/influential-figures/george-clutesi.

“Get your bannock and tea - CBC Archives.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 9 Mar. 2017, http://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/get-your-bannock-and-tea.

Obituary: Noted Painter, Actor.” Toronto Star, 3 Mar. 1988, p. A19.

Additional Resources:

For a discussion of Clutesi as an author performing at Expo 67 see:

Herder, Scott. Literature as a technology of commemoration at Expo 67. University of Toronto Quarterly, vol. 92, no. 1, 2023, pp.1–26.

https://doi.org/10.3138/utq.92.1.01

This study highlights the significance of literature to Expo 67 and the tradition of world exhibitions. Like the world’s fairs before it, the Montreal exhibition promoted literature as a technology of national progress. Yet Expo 67 reflected simultaneously the contemporary anxieties about technology and nationhood expounded by George Grant in the 1960s in contrast with the celebration of nationalism and technological progress bound together in the tradition of world’s fairs. Though world’s fairs had depicted the educational utility of literature throughout their tradition, Expo 67 emphasized literature more than any world exhibition had to that point. Its theme, Terre des hommes, drawn from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s autobiographical narrative, its literature conferences and poetry performances, and the broader textuality of Expo 67 as a “total environment” were intended to deploy texts in promotion of the ideals of universal humanism. However, I find that poetry performances by Michèle Lalonde, George Clutesi, and Duke Redbird contradicted the event’s stated ideals by spotlighting the negative effects of technology and ongoing colonial violence. I argue further that large-scale literature exhibits at Expo 67 resisted the humanist ideals of the event by continuing the world exhibition convention of treating literary works as an educative technology of national progress. As a result, I find that Canadian literature at Expo 67 complicates the Canadian collective memory of the event and

the 1967 Centennial Year.

For quotations by Clutesi who advocates for fair compensation for Indigenous artists:

Roth, Solen. “Can Capitalism be Decolonized? Recentering Indigenous Peoples, Values, and Ways of Life in the Canadian Art Market.” American Indian Quarterly, vol 43, no. 3, 2019, p.306.

https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.43.3.0306

For a biography of Clutesi in the context of the Canadian Indigenous art market, see:

Carocci, Max., and Stephanie Pratt, Eds. & Pratt, S. (Eds.). (2024). Art, Observation, and an Anthropology of Illustration. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2022.

Endnotes:

1. Also recorded as “go home and dance” in some articles.

George Clutesi entry by Kimberley John, September 2018. Updated April 2019. Kimberley is an alumnus of SFU, graduating with a Double Major in Health Sciences and Indigenous Studies. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2016 to 2020.

Additional Resources collected by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli is an alumnus of McGill University, graduating with an M.Mus. in Jazz Performance in Summer 2024.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca with any comments or corrections.